With Anwar Chaudhary’s death on March 6, at the age of 68, an era came to a close. He belonged to a generation of post-partition Punjabis who grew up with high hopes of a just society and open politics. They spent their formidable years in the activism of late 1960s and early 70s but, once the power brokers had filled their plates, they were left alone in the land of ever-growing pain and delusion with shattered pieces of those dreams.

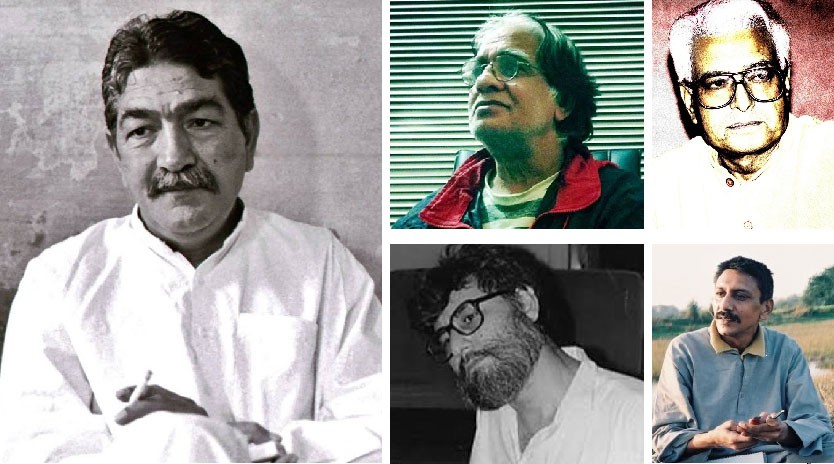

Painters Ahmed Zoay and Iqbal Rashid (Bãla), singer and activist Tahir Yasoob Shah and journalist Zafaryab Ahmed are a few of those disconsolate souls who were lost in the wilderness of a socialist struggle and political activism. A recollection of Anwar Chaudhary brings all these wanderers to mind.

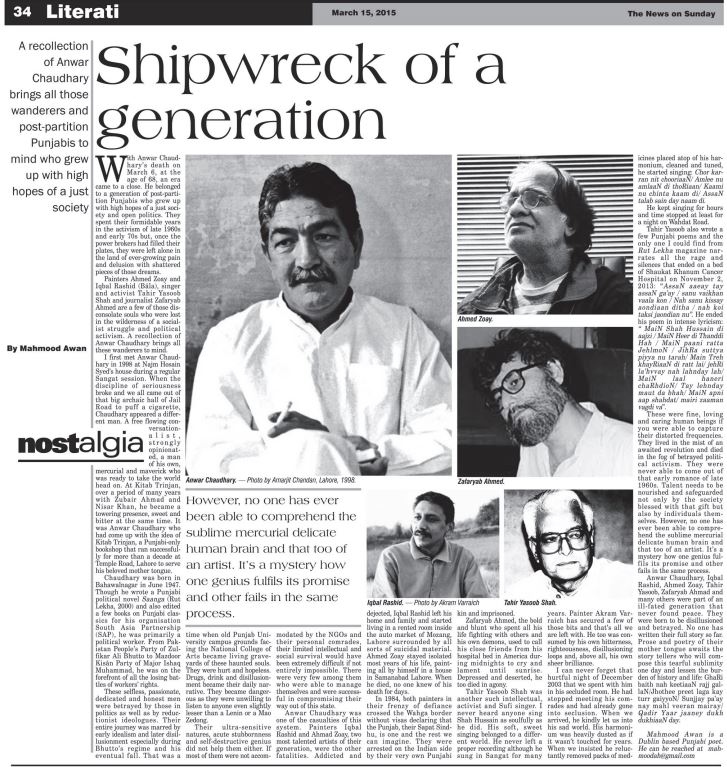

I first met Anwar Chaudhary in 1998 at Najm Hosain Syed’s house during a regular Sangat session. When the discipline of seriousness broke and we all came out of that big archaic hall of Jail Road to puff a cigarette, Chaudhary appeared a different man. A free flowing conversationalist, strongly opinionated, a man of his own, mercurial and maverick who was ready to take the world head on. At Kitab Trinjan, over a period of many years with Zubair Ahmad and Nisar Khan, he became a towering presence, sweet and bitter at the same time. It was Anwar Chaudhary who had come up with the idea of Kitab Trinjan, a Punjabi-only bookshop that ran successfully for more than a decade at Temple Road, Lahore to serve his beloved mother tongue.

Chaudhary was born in Bahawalnagar in June 1947. Though he wrote a Punjabi political novel Saanga (Rut Lekha, 2000) and also edited a few books on Punjabi classics for his organisation South Asia Partnership (SAP), he was primarily a political worker. From Pakistan People’s Party of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to Mazdoor Kisãn Party of Major Ishaq Muhammad, he was on the forefront of all the losing battles of workers’ rights.

Their ultra-sensitive natures, acute stubbornness and self-destructive genius did not help them either. If most of them were not accommodated by the NGOs and their personal comrades, their limited intellectual and social survival would have been extremely difficult if not entirely impossible. There were very few among them who were able to manage themselves and were successful in compromising their way out of this state.

Anwar Chaudhary was one of the casualties of this system. Painters Iqbal Rashid and Ahmad Zoay, two most talented artists of their generation, were the other fatalities. Addicted and dejected, Iqbal Rashid left his home and family and started living in a rented room inside the auto market of Mozang, Lahore surrounded by all sorts of suicidal material. Ahmed Zoay stayed isolated most years of his life, painting all by himself in a house in Samanabad Lahore. When he died, no one knew of his death for days.

In 1984, both painters in their frenzy of defiance crossed the Wahga border without visas declaring that the Punjab, their Sapat Sindhu, is one and the rest we can imagine. They were arrested on the Indian side by their very own Punjabi kin and imprisoned.

Zafaryab Ahmed, the bold and blunt who spent all his life fighting with others and his own demons, used to call his close friends from his hospital bed in America during midnights to cry and lament until sunrise. Depressed and deserted, he too died in agony.

Tahir Yasoob Shah was another such intellectual, activist and Sufi singer. I never heard anyone sing Shah Hussain as soulfully as he did. His soft, sweet singing belonged to a different world. He never left a proper recording although he sung in Sangat for many years. Painter Akram Varraich has secured a few of those bits and that’s all we are left with. He too was consumed by his own bitterness, righteousness, disillusioning loops and, above all, his own sheer brilliance.

I can never forget that hurtful night of December 2003 that we spent with him in his secluded room. He had stopped meeting his comrades and had already gone into seclusion. When we arrived, he kindly let us into his sad world. His harmonium was heavily dusted as if it wasn’t touched for years. When we insisted he reluctantly removed packs of medicines placed atop of his harmonium, cleaned and tuned, he started singing: Chor karran nit chooriaaN/ Amlee nu amlaaN di thoRiaan/ Kaami nu chinta kaam di/ AssaN talab sain day naam di.

He kept singing for hours and time stopped at least for a night on Wahdat Road.

Tahir Yasoob also wrote a few Punjabi poems and the only one I could find from Rut Lekha magazine narrates all the rage and silences that ended on a bed of Shaukat Khanum Cancer Hospital on November 2, 2013: “AssaN aaeay tay assaN ga’ay / sanu vaikhan vaala kon / Nah sanu kissay aondiaan ditha / nah koi taksi jaondian nu”. He ended his poem in intense lyricism: ” MaiN Shah Hussain di aajzi / MaiN Heer di Thanddi Hah / MaiN paani ratta JehlmoN / JihRa suttya piyya nu tarah/ Main Treh khayRiaaN di ratt lai/ jehRi la’hvvay nah lahnday lah/ MaiN laal haneri chaRhdioN/ Tay lehnday maut da bhah/ MaiN apni aap shahdat/ mairi zaaman vagdi va“.

These were fine, loving and caring human beings if you were able to capture their distorted frequencies. They lived in the mist of an awaited revolution and died in the fog of betrayed political activism. They were never able to come out of that early romance of late 1960s. Talent needs to be nourished and safeguarded not only by the society blessed with that gift but also by individuals themselves. However, no one has ever been able to comprehend the sublime mercurial delicate human brain and that too of an artist. It’s a mystery how one genius fulfills its promise and other fails in the same process.

Anwar Chaudhary, Iqbal Rashid, Ahmed Zoay, Tahir Yasoob, Zafaryab Ahmad and many others were part of an ill-fated generation that never found peace. They were born to be disillusioned and betrayed. No one has written their full story so far. Prose and poetry of their mother tongue awaits the story tellers who will compose this tearful sublimity one day and lessen the burden of history and life: GhaRi baith nah keetiaaN rajj gallaN/Jhothee preet laga kay turr gaiyyoN/ Sunjjay pa’ay nay mahl veeran mairay/ Qadir Yaar jaaney dukh dukhiaaN day.

Published on 15th March 2015 in The News on Sunday.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/558228-post-partition-punjabis-shipwreck-of-a-generation