Mahmood Awan (The News on Sunday, 31st August 2014)

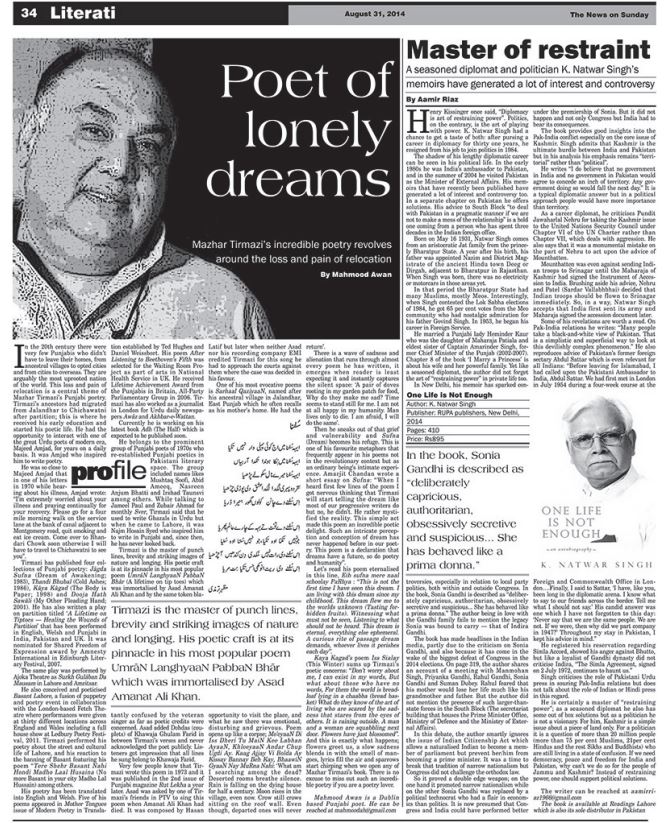

In the 20th century there were very few Punjabis who didn’t have to leave their homes, from ancestral villages to opted cities and from cities to overseas. They are arguably the most uprooted nation of the world. This loss and pain of relocation is a central theme of Mazhar Tirmazi’s Punjabi poetry. Tirmazi’s ancestors had migrated from Jalandhar to Chichawatni after partition; this is where he received his early education and started his poetic life. He had the opportunity to interact with one of the great Urdu poets of modern era, Majeed Amjad, for years on a daily basis. It was Amjad who inspired him to write poetry.

He was so close to Majeed Amjad that in one of his letters in 1970 while hearing about his illness, Amjad wrote: “I’m extremely worried about your illness and praying continually for your recovery. Please go for a four mile morning walk on the service lane at the bank of canal adjacent to Montgomery road, quit smoking and eat ice cream. Come over to Bhandari Chowk soon otherwise I will have to travel to Chichawatni to see you”.

Tirmazi has published four collections of Punjabi poetry: Jãgda Sufna (Dream of Awakening; 1983), Thandi Bhubal (Cold Ashes; 1986), Kãya Kãgad (The Body is Paper; 1998) and Dooja Hath Sawãli (My Other Pleading Hand; 2001). He has also written a play on partition titled ‘A Lifetime on Tiptoes — Healing the Wounds of Partition’ that has been performed in English, Welsh and Punjabi in India, Pakistan and UK. It was nominated for Shared Freedom of Expression award by Amnesty International in Edinburgh Literary Festival, 2007.

The same play was performed by Ajoka Theatre as Surkh Gulãban Da Mausam in Lahore and Amritsar.

He also conceived and poeticised Basant Lahore, a fusion of puppetry and poetry event in collaboration with the London-based Fetch Theatre where performances were given at thirty different locations across England and Wales including a full house show at Ledbury Poetry Festival, 2011. Tirmazi performed his poetry about the street and cultural life of Lahore, and his reaction to the banning of Basant featuring his poem “Tere Shehr Basant Nahi Hondi Madho Laal Husaina (No more Basant in your city Madho Lal Hussain) among others.

His poetry has been translated into English and Welsh. Five of his poems appeared in Mother Tongues issue of Modern Poetry in Translation established by Ted Hughes and Daniel Weissbort. His poem After Listening to Beethoven’s Fifth was selected for the Waiting Room Project as part of arts in National Health Service in UK. He received Lifetime Achievement Award from the Punjabis in Britain, All-Party Parliamentary Group in 2006. Tirmazi has also worked as a journalist in London for Urdu daily newspapers Awãz and Akhbar-e-Wattan.

Currently he is working on his latest book Adh (The Half) which is expected to be published soon.

He belongs to the prominent group of Punjabi poets of 1970s who re-established Punjabi poetics in Pakistani literary space. The group included names likes Mushtaq Soofi, Abid Ameeq, Nasreen Anjum Bhatti and Irshad Taunsvi among others. While talking to Jameel Paul and Zubair Ahmad for monthly Sver, Tirmazi said that he used to write Ghazals in Urdu but when he came to Lahore, it was Najm Hosain Syed who inspired him to write in Punjabi and, since then, he has never looked back.

Tirmazi is the master of punch lines, brevity and striking images of nature and longing. His poetic craft is at its pinnacle in his most popular poem UmrãN LanghyaaN PabbaN Bhãr (A lifetime on tip toes) which was immortalised by Asad Amanat Ali Khan and by the same token blatantly confused by the veteran singer as far as poetic credits were concerned. Asad added Dohdas (couplets) of Khawaja Ghulam Farid in between Tirmazi’s verses and never acknowledged the poet publicly. Listeners got impression that all lines he sung belong to Khawaja Farid.

Very few people know that Tirmazi wrote this poem in 1973 and it was published in the 2nd issue of Punjabi magazine Rut Lekha a year later. Asad was asked by one of Tirmazi’s friends in PTV to sing this poem when Amanat Ali Khan had died. It was composed by Hasan Latif but later when neither Asad nor his recording company EMI credited Tirmazi for this song he had to approach the courts against them where the case was decided in his favour.

One of his most evocative poems is Sarhaal QaziyaaN, named after his ancestral village in Jalandhar, East Punjab which he often recalls as his mother’s home. He had the opportunity to visit the place, and what he saw there was emotional, disturbing and grievous. Poem opens up like a corpse; Mo’eyaaN Di Iss Dheri Tu MaiN Kee Labhan AyaaN, KhloeyaaN Andar Chup Ugdi Ay. Kaag Ajjay Vi Bolda Ay Kissay Bannay Beh Kay, BhaawiN GyaaN Nay MuRna Nahi: ‘What am I searching among the dead? Deserted rooms breathe silence. Rain is falling on the dying house for half a century. Moon rises in the village, even now. Crow still crows sitting on the roof wall. Even though, departed ones will never return’.

There is a wave of sadness and alienation that runs through almost every poem he has written, it emerges when reader is least expecting it and instantly captures the silent space: ‘A pair of doves rooting in my garden patch for food, Why do they make me sad? Time seems to stand still for me. I am not at all happy in my humanity. Man lives only to die. I am afraid, I will do the same’.

Then he sneaks out of that grief and vulnerability and Sufna (Dream) becomes his refuge. This is one of his favourite metaphors that frequently appear in his poems not in the revolutionary context but as an ordinary being’s intimate experience. Amarjit Chandan wrote a short essay on Sufna: “When I heard first few lines of the poem I got nervous thinking that Tirmazi will start telling the dream like most of our progressive writers do but no, he didn’t. He rather mystified the reality. This simple act made this poem an incredible poetic delight. Such an intricate perception and conception of dream has never happened before in our poetry. This poem is a declaration that dreams have a future, so do poetry and humanity”.

Let’s read his poem eternalised in this line, Eih sufna mere naal schoolay PaRhya : “This is not the first time I have seen this dream. I am living with this dream since my childhood. This dream flew me to the worlds unknown (Tasting forbidden fruits). Witnessing what must not be seen, Listening to what should not be heard. This dream is eternal, everything else ephemeral. A curious rite of passage dream demands, whoever lives it perishes each day”.

Kaya Kagad’s poem Iss Sialay (This Winter) sums up Tirmazi’s poetic concerns: “Don’t worry about me, I can exist in my words, But what about those who have no words, For them the world is bread-loaf lying in a chaabba (bread basket) What do they know of the art of living who are scared by the sadness that stares from the eyes of others. It is raining outside. A man and a woman are squabbling next door. Flowers have just blossomed”. And this is exactly what happens; flowers greet us, a slow sadness blends in with the smell of mangoes, lyrics fill the air and sparrows start chirping when we open any of Mazhar Tirmazi’s book. There is no excuse to miss out such an incredible poetry if you are a poetry lover.

Published on 31st August 2014 in The News on Sunday.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/556963-mazhar-tirmazi-poet-of-lonely-dreams