Mahmood Awan (The News on Sunday, 22nd October 2017)

Punjab has been living with an injured soul since its annexation by the British colonialists in 1849. Punjabis were divided, reduced, and humiliated through these years and accelerated efforts were made to partition their collective heritage and culture along reductionist religious lines. However, the collective cultural-spiritual thread among Punjabis could never be fully broken. When the Indian army stormed Darbar Sahib on June 6, 1984, it was not only the Sikhs who felt that pain and humiliation, their fellow Punjabis on this side of the border experienced it as well.

Late Afzal Ahsan Randhawa’s poem Navãṉ Ghalughãra (The Latest Holocaust) written on June 9, 1984 is a testament to that feeling.

This pain was aggravated when an anti-Sikh pogrom across India was organised and launched by the then ruling political party. After Indira Gandhi’s assassination, rioting led by Hindu mobs went unchecked during the first week of November 1984.

Indira Gandhi was marketed as ‘Mother India’ and it was on her direct orders that the destruction of Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple, Amritsar) was executed. Poet Harbhajan Singh remembered her in the following words: “Jay jay maata jay matrai / Jagg tay hoNi nah tairay jahi/Harminder di karran juhaari/tu aaeeṉ karr tank svaari”. He rhymed again: “Maaṉ aiṉ jaaṉ matrai/Sanu wadh kay dhuppay suttya/ naalay aakheeṉ zakhmaaṉ walya/ aa tainu mallham lagaawaaṉ”.

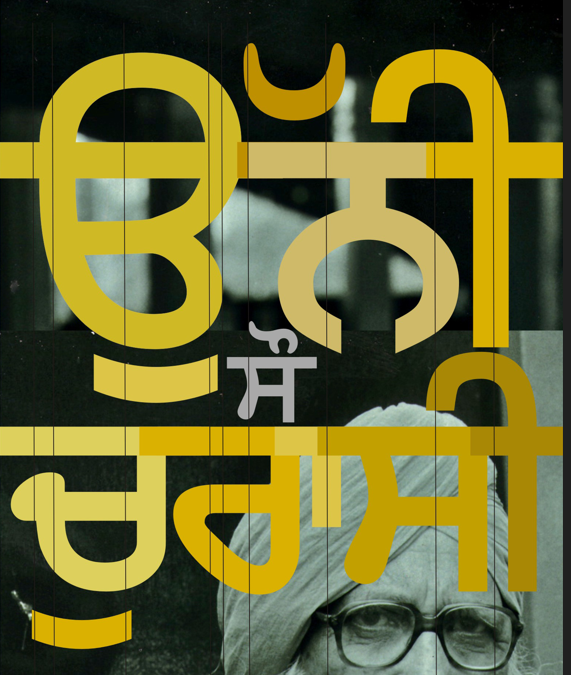

Unni Sau Churasi (1984) is a collection of 48 poems by Harbhajan Singh (1920-2002) about the anti-Sikh pogroms of 1984. This book also includes three of his essays, taken from his autobiography Chola taakiaaN waala; 1994, and one short interview.

Amarjit Chandan has edited and introduced this book with an insightful and must-read introduction and award-winning filmmaker Gurvinder Singh designed the book cover. This is the first time that all these poems are being published as a collection and the credit goes to Chandan, and Harbhajan Singh’s family for allowing these to be published. Fear of state oppression may be one reason that these poems took so long to be published as a book. Harbhajan Singh himself indirectly pointed this out in one of his essays while talking about the publisher of Aarsi magazine, Bhapa Pritam Singh, who declined to publish one of his 1984 poems titled ‘Jay jay maata jay matrai’.

Harbhajan Singh spent his childhood years in Ichhra, Lahore and after Partition settled in Delhi. He wrote more than 50 books of Punjabi and taught for Delhi University’s Department of Modern Indian languages programme. Singh belonged to that small group of intellectuals who were against extreme positions of both the Indian state and Sikh militants. He conveyed that openly in his poems: “Nah Bullehia assiṉ Bhindranwalay/ nah assiṉ Indiraaṉ waalay” or “Iknaa har kay bandday kohay/ Ikna har kay Manddir/ dohaaṉ day wich koi nah aisa/ jiss nu apNa kehyyay“. When DIG of Jalandhar Police, A.S Atwal (rumoured to be connected with fake encounters), was shot dead at the entrance of Golden Temple on April 25, 1983, it was Harbhajan Singh who wrote these lines: “Eh anhoNi taiṉ darr hoee/dharram kodharram nitaaro/ tairi deohRi daagh pia hay /Kirpa sehat utaaro.”

Before I delve further into Harbhajan Singh’s poems, I feel it necessary to go through events that led up to 1984. Khushwant Singh in his book My Bleeding Punjab talked about it in detail. The book starts by ridiculing Khalistan and its supporters in these words: “I have failed to meet a single individual who could rationally explain to me its geographical boundaries and its proposed political and economic setup [including] my two long meetings with Ganga Singh Dhillon.”

Khushwant Singh further adds that the “First detailed map of Khalistan that I have seen was published in England and priced at £2. According to that map, Khalistan will include Jammu, the whole of Himachal Pardesh, Haryana, Delhi, chunks of Uttar Pardesh, Rajasthan and Saurashtra to give the state an outlet to the sea. It has ten signatories led by a gentleman named Jaswant Singh Thekedar styling himself as Defence Minister of Khalistan Government”.

Khushwant Singh then adds that proclamation of the Sovereign Republic of Khalistan was first declared in 1969 by Dr Jagjit Singh Chauhan, once Finance Minister of East Punjab, then living in exile in London. He was supported by the Sikh diaspora and his lead supporter-collaborator was Washington D.C.-based businessman Ganga Singh Dhillon, who openly believed that the Sikhs are not just a religious community but a separate nation and from 1969 to Jarnail Singh Bhindranawala’s rise as head of Dam Dami Taksal in August 1977, the idea of Khalistan was just a diaspora illusion.

Bhindranawala was born in 1947 in village Rode in Moga district and was the youngest of seven sons of a poor farmer, Joginder Singh. He rose to prominence during his follower’s confrontation with a Sikh breakaway subsect of Nirankaris. Many writers including Khushwant Singh believe that Bhindranawala was supported and exploited by Indira Gandhi and her Congress Party whip, Giani Zail Singh, to weaken and counter the influence of the Akali movement in East Punjab – the Akali movement was a campaign to bring reform in India’s gurdwaras. During those years of insurgency over 10,000 innocent people were killed including Sant Harchand Singh Longowal, Master Tara Singh’s daughter Rajinde Kaur, Preet Lari editor Sumeet Singh, Punjabi poet Pash, VN Tiwari and Lala Jagat Narain of Hind Samachar.

Bhindranawala’s movement was an armed militant movement with roots in rural East Punjab. The transformation of Sikhs from a rather pacifist to a militant sect had started under the sixth Guru Hargobind who succeeded his father Guru Arjun (the first martyr of Sikhs) who was unjustly assassinated by the Mughal Governor of Lahore in 1606. Then after the execution of ninth Guru, Tegh Bahadur, in Delhi by Mughal emperor, came the 10th Guru, Gobind, who succeeded his father at the age of 9 and grew to finalise the Sikh religion and became the founder of the Khalsa (the pure).

The 10th Guru was also assassinated at the behest of Mughal rulers. All these injustices pushed Sikhs towards a militant formation that culminated successfully into Ranjit Singh’s Punjab Kingdom.

Nevertheless, with the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, Sikhs started going back to Hinduism and according to Khushwant Singh, it was Lord Dalhousi who gave the Khalsas a second lease of life by employing them in huge numbers in the East India Company army and giving preferences to ‘Kesadhaari Khalsa’. Also, Sikhs who did not support 1857 were rewarded with large estates in new Punjab colonies and more employments in Army and Police. Khushwant Singh further quotes an interesting note of Lord Dalhousie in his book: “Their great guru Govind sought to abolish caste and in great degree succeeded. They are however, gradually relapsing into Hinduism, and even when they continue as Sikhs, they are yearly Hindufied more and more; so much so that, that sir George Clerk (Governor of Bombay 1847-48) has said that in 50 years the sect of Sikhs would have disappeared.”

However, Sikhs survived and survived well under the British rule. It was during Partition discussions that the Sikh political leadership made a mistake and their convert leader Master Tara Singh (who was a Hindu Malhotra until the age of 11) put his complete trust in Nehru’s Congress, and Nehru and Congress betrayed them at the very beginning by rejecting their demand for a separate Punjabi subah.

Akali Dal (Akalis) took to the streets by using language as a campaigning tool to secure a separate Sikh majority state. They eventually succeeded in getting a separate Punjabi subah in 1966 largely due to the IndoPak war of 1965 and because Nehru had died by then. Punjab was divided further into Haryana and Himachal Pradesh leaving the present day East Punjab with only 15 per cent of the area of pre-1947 undivided Punjab.

In the late 1970s, Akalis were agitating again with Dharam Yudho, Rasta Roko, Nehr Roko processions to demand what had been set in the Anandpur resolution which was not accepted by the Central Government when Jarnail Singh Bhindranwala rose to fame with his furious anti-Hindu sermons. Akalis were demanding a readjustment of boundaries, a resolution of the river water disputes and amendments in article 25 which were being played down by Indira Gandhi. In this intense environment, on February 25, 1984, Akalis burnt article 25 of the Indian constitution that terms Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhs, as Hindus.

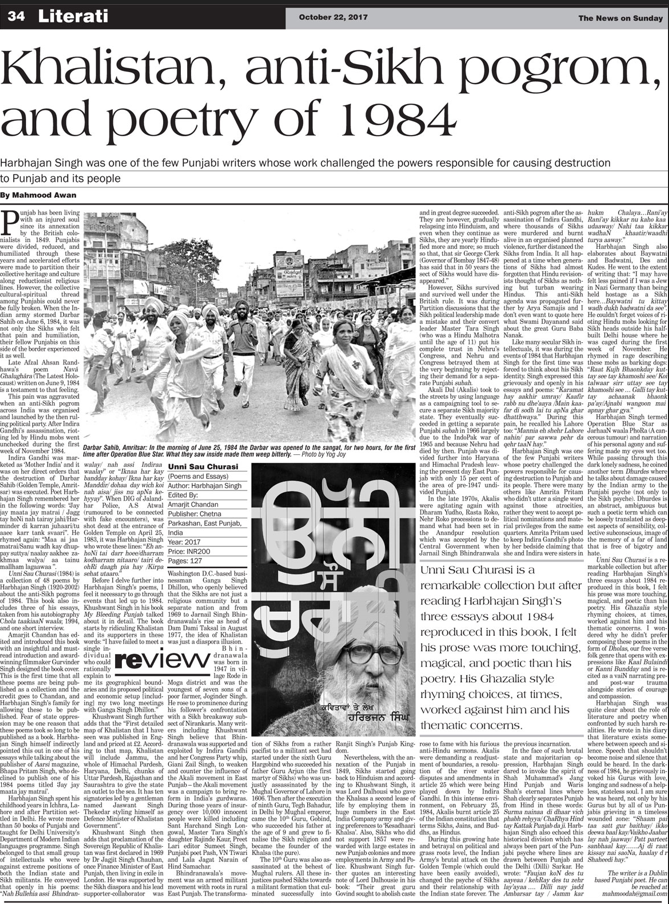

During this growing hate and betrayal on political and grass roots level, the Indian Army’s brutal attack on the Golden Temple (which could have been easily avoided), changed the psyche of Sikhs and their relationship with the Indian state forever. The anti-Sikh pogrom after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, where thousands of Sikhs were murdered and burnt alive in an organised planned violence, further distanced the Sikhs from India. It all happened at a time when generations of Sikhs had almost forgotten that Hindu revisionists thought of Sikhs as nothing but turban wearing Hindus. This anti-Sikh agenda was propagated further by Arya Samajis and I don’t even want to quote here what Swami Dayanand said about the great Guru Baba Nanak.

Like many secular Sikh intellectuals, it was during the events of 1984 that Harbhajan Singh for the first time was forced to think about his Sikh identity. Singh expressed this grievously and openly in his essays and poems: “Karamat hay aakhir umray/ Kaafir rabb nu dhe’aaya /Main kaafar di sodh lai tu apNa ghar dhatthwaya.” During this pain, he recalled his Lahore too: “Mannia eh shehr Lahore nahin/ par sawwa pehr da qehr taaN hay.”

Harbhajan Singh was one of the few Punjabi writers whose poetry challenged the powers responsible for causing destruction to Punjab and its people. There were many others like Amrita Pritam who didn’t utter a single word against those atrocities, rather they went to accept political nominations and material privileges from the same quarters. Amrita Pritam used to keep Indira Gandhi’s photo by her bedside claiming that she and Indira were sisters in the previous incarnation.

In the face of such brutal state and majoritarian oppression, Harbhajan Singh dared to invoke the spirit of Shah Muhammad’s Jang Hind Punjab and Waris Shah’s eternal lines where Shah clearly separates Punjab from Hind in these words: Surma nainaaṉ di dhaar vich phabh rehyya/ ChaRhya Hind tay Kattak Punjab da ji. Harbhajan Singh also echoed this historical division which has always been part of the Punjabi psyche where lines are drawn between Punjab and the Delhi (Dilli) Sarkar. He wrote: “Faujan koN des tu aayeaaṉ/ kehRay des tu zehr lay’ayaaṉ…. Dilli nay jadd Ambarsar tay / Jamm kar hukm Chalaya…Rani’ay Rani’ay kikkar nu kaho kaaṉ udaaway/ Nahi taaṉ kikkar wadhaN khaatir/waadhi turya aaway.”

Harbhajan Singh also elaborates about Baywatni and Badwatni, Des and Kudes. He went to the extent of writing that: “I may have felt less pained if I was a Jew in Nazi Germany than being held hostage as a Sikh here…Baywatni tu kittay wadh dukh badwatni da see”. He couldn’t forget voices of rioting Hindu mobs looking for Sikh heads outside his half-built Delhi house where he was caged during the first week of November. He rhymed in rage describing these mobs as barking dogs: “Raat Kujh Bhaonkday kuttay see tay khamoshi see/ Koi talwaar sirr uttay see tay khamoshi see … Galli tay kuttay achaanak bhaonk pa’ay/Ajnabi wangoon maiṉ apnay ghar gya.”

Harbhajan Singh termed Operation Blue Star as JarhaaN waala PhoRa (A cancerous tumour) and narration of his personal agony and suffering made my eyes wet too. While passing through this dark lonely sadness, he coined another term Dhurdes where he talks about damage caused by the Indian army to the Punjabi psyche (not only to the Sikh psyche). Dhurdes is an abstract, ambiguous but such a poetic term which can be loosely translated as deepest aspects of sensibility, collective subconscious, image of the memory of a far of land that is free of bigotry and hate.

Unni Sau Churasi is a remarkable collection but after reading Harbhajan Singh’s three essays about 1984 reproduced in this book, I felt his prose was more touching, magical, and poetic than his poetry. His Ghazalia style rhyming choices, at times, worked against him and his thematic concerns. I wondered why he didn’t prefer composing these poems in the form of Dholas, our free verse folk genre that opens with expressions like Kaal Bulaindi or Kanni Bundday and is recited as a vaiN narrating pre-and post-war trauma alongside stories of courage and compassion.

Harbhajan Singh was quite clear about the role of literature and poetry when confronted by such harsh realities. He wrote in his diary that literature exists somewhere between speech and silence. Speech that shouldn’t become noise and silence that could be heard. In the darkness of 1984, he grievously invoked his Gurus with love, longing and sadness of a helpless, stateless soul. I am sure he was heard, not only by his Gurus but by all of us Punjabis grieving in a timeless wounded zone: “Shaam pai taaṉ satt gur baithay/ ikko deewa baal kay/Vaikho Jaabar lay nah jaaway/ Patt parteet sanbhaal kay……Aj di raat kissay nai saoNa, haalay dṳr Shaheedi hay.”

Unni Sau Churasi (Poems and Essays)

Author: Harbhajan Singh

Edited By: Amarjit Chandan

Publisher: Chetna Parkashan, East Punjab, India

Year: 2017

Price: INR200

Pages: 127

Published on 22nd October 2017 in The News on Sunday.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/564232-khalistan-anti-sikh-pogrom-poetry-1984