Mahmood Awan (The News on Sunday, 12th October 2014)

Poetry is what is lost in translation, claimed Robert Frost while Joseph Brodsky simply reversed the argument: “Poetry is what is gained in translation”; but Latin, the ancient language of Brodsky’s beloved Venice kept insisting: “Traduttore, traditore” (translator is a traitor).

It was then Susan Sontag who summed up the whole debate with a touch of poetic brevity as she believed not in the foreignness of languages but their oneness: “Every language is part of Language, which is larger than any single language.” This unification and singularity of the lingual experience created that global literary space in which we inhale the pleasures of weightlessness. This immensely diverse multilingual world would never have been the same without translations of Rumi, Chekhov, Proust, Kafka, Mahfouz, Neruda, Marquez and so many others.

International Translation Day is celebrated every year on September 30 in the memory of St. Jerome, the priest who translated Bible into Latin and is considered the patron saint of translators. Fédération Internationale des Traducteurs/ International Federation of Translators (FIT) started promoting this day since its inception but in 1991 FIT launched the idea of an officially recognised International Translation Day to appreciate the profession that has become an essential part of today’s globalised world.

Translation of classical, religious and modern Punjabi literature started in the late 19th century sponsored by the British colonial authorities. The colonial bureaucrats and missionaries like Arthur Macauliffe and Ernest Trumpp undertook this task with the help of local Punjabi scholars. Translations of religious books started as early as 1850s in the Punjab.

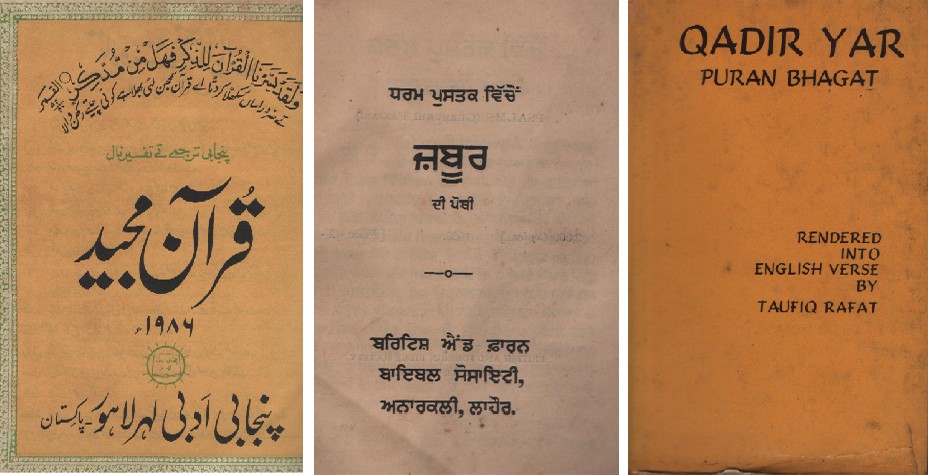

John Newton of the Ludhiana Christian Mission published the first-ever Punjabi translation of the New Testament titled Anjeel [after French — Evengile] in 1851. Trumpp was the first to translate Adi Granth into English in 1870. I found a copy of Zabur (the Old Testament) translated into Punjabi in Gurmukhi script published by British & Foreign Bible Society Anarkali, Lahore in 1930. Without any colonial support, it was Maulvi Hidayat-ullah of Sialkot who started translating Holy Quran into Punjabi (in the Farsi script) in 1887 on his own.

Within a generation, a new crop of native Punjabi scholars appeared on the scene that was well-versed in English; they started translating Punjabi classical and modern Punjabi literature into English. Puran Singh, the poet, is considered a pioneer in the field. A league of creative writers like Teja Singh, Mohan Singh Uberoi Diwana and Sant Singh Sekhon worked intensively on translations later. East Punjabis, as in all matters of Punjabi pride, took lead in the venture as well.

Literary texts from Punjabi were introduced in the post-graduate university curricula in the courses on “literature in translation’ in all universities in East Punjab after partition. Scholars from the three universities have translated much of Punjabi contemporary fiction and poetry into English. Sahitya Akademi (Indian Academy of Letters) and National Book Trust have published many English translations of Punjabi fiction.

Lately, private publishing houses and international journals have also shown much interest in contemporary Punjabi literature and titles by Amrita Pritam, Gurdial Singh, Harbahjan Singh, Amarjit Chandan, Lal Singh Dil, Pash and Surjit Patar have been published. Amrita Pritam was translated by Charles Bracsh, Mohan Singh and Pash by Tejwant Singh Gill, Lal Singh Dil by Nirupama Dutt and Trilok Chand Ghai while Shiv Kumar’s epic poem ‘Loona’ was translated by Sant Singh Sekhon.

Not surprisingly, the most contemptuous attitude was shown by us, the West Punjabis. There isn’t a single anthology or collection of West Punjabi poetry or fiction available in English. Some of the classics have been translated but not much of the contemporary literature. Irfan Malik and Waqas Khwaja are the only two west Punjabis who initiated translations of contemporary Punjabi Poetry.

Malik guest edited English literary journal Salamander (New Jersey. USA. 1995) that included poems by Najm Hosian Syed, Munir Niazi, Abid Ameeq, Mushtaq Soofi and Zubair Ahmad while Waqas Khwaja translated and published poetry of Mushtaq Soofi, Nasreen Anjum Bhatti and Ustad Daman in Cactus, Atlanta Review and South Asian Literary Review.

Some poems of Najm Hosain Syed were translated by Zubair Ahmad and Fauzia Rafique for Journal of Punjab Studies (University of California, Santa Barbra) in 2006. While Taufiq Rafat (Bulleh Shah and Qadir Yaar), Athar Tahir (Qadir Yaar), Shahzad Qaisar (Khawaja Ghulam Farid), Ghulam Yaqoob Anwar (Shah Hussain) and Muzaffar Ghaffar (Bulleh Shah, Heer Damodar) have translated Punjabi Classical poetry.

Punjabi fiction is also finding its way into the translation world. Following major anthologies contain translations of Punjabi short stories: Land of Five Rivers: Short Stories by the Best Known Writers from the Punjab (Orient Paperbacks, 1992) by Khushwant Singh, A letter from India: Contemporary short stories from Pakistan (Penguin India. 2004) by Moazzam Sheikh and Stories of the Soil (Penguin, 2010) by Nirupama Dutt. In East Punjab almost all major Punjabi writers have been translated but on the western side Fakhar Zaman is perhaps the only Punjabi writer who has got almost all his novels and poetry translated into English.

Most neglected aspect of this translation endeavour is the modern Punjabi Poetry and fiction of Pakistan that has been neglected by writers themselves as well as by our bilingual scholars. We all know that there has never been any institutional support available to the Punjabi language.

Those institutions whose responsibility was to protect and strengthen our native languages are hell-bent on burying them. Pakistan Academy of Letters’ collaborative translation work Modern Poetry of Pakistan (Dalkey Archive Press. 2010) embodies that mindset. It was edited by Iftikhar Arif and Translation editor was Waqas Khwaja. Selection of the entire anthology was exclusively done by Arif and his generosity could only afford four Punjabi Poets to represent a population of 101 million Punjabis of Pakistan and much to my horror Najm Hosain Syed, Mushtaq Soofi, Mazhar Tirmazi, Irfan Malik, Raja Sadiqullah, Ashu Lal and Abid Ameeq failed to make into his ‘modern list’. There are six poems of Yasmeen Hameed in this selection but only two of Ahmad Rahi’s and three of Ustad Daman’s (who was initially excluded by the editor and ex-Chairman of the Academy).

Therefore, a proficient translation authority is needed that is not self-serving and prejudiced. We need to link ourselves with other cultures through literature and this can only happen if we can produce competent and compelling translations which are accessible to the people in the language of translation so that they can read and enjoy the text as their own. Academic, Victorian and serviceable translations will be pointless and counterproductive. There is an urgent need to connect with the global community with all our native charm. We need to tell our stories because if we will not tell our own stories, no one else will.

Published on 12th October 2014 in The News on Sunday.