Mahmood Awan (The News on Sunday, 26th January 2020)

A writer can be anything; a revolutionary, a spiritual guide, a thought leader and even founder of a new religion. However, if such a leader identifies himself as a writer, he will be considered an artist, first and foremost by his nonconformist, nonreligious readers, who will be more interested in his artistic paraphernalia. As it’s the skills set, the hard-earned art of writing that provides the basis for the successful transmission of a revolutionary idea or a divine thought.

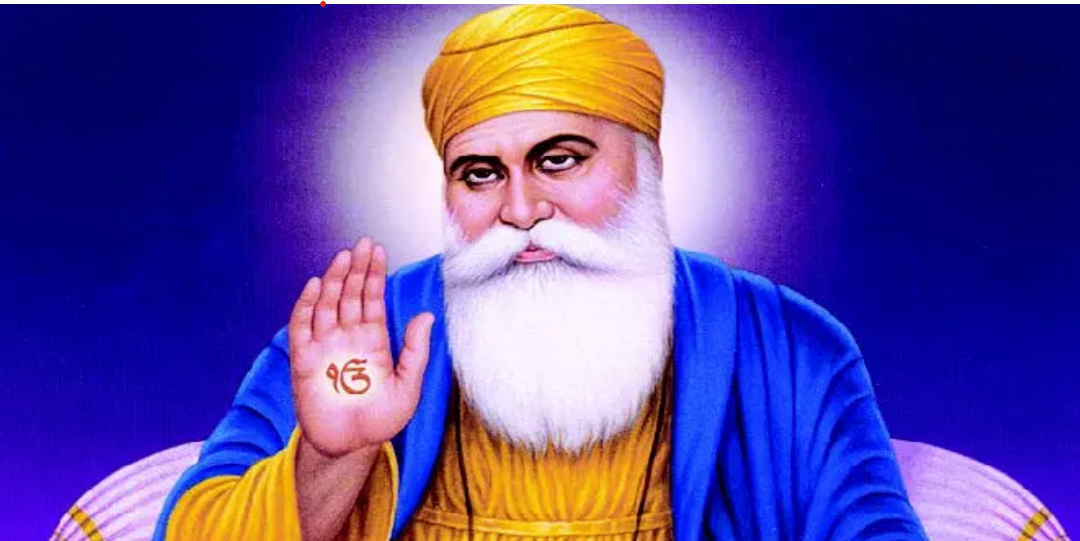

Baba Nanak (1469-1539) is one such personality. His overwhelming sense of appreciation for everything related to the process and art of writing, as depicted in the lines below, gives his readers the liberty to start their literary travels free of any religious dogmas.

For example, he writes, Dhan so kaagad, kalam dhan, dhan bhaanda, dhan mass/Dhan likhaari Nanaka, jin naam likhaya sach

(Blessed is the paper, blessed is the pen, blessed the inkpot and blessed is the ink/Blessed is the writer, O Nanak, who writes the truth).

Moving on to the importance of artistic perfection, he reiterates: Jay ik hoay taa(n) uggvay, ruttee(n) hoo rut hoay/Nanak paahay baahraa, koray rang nah soay

(If the seed is whole, and it is the proper season, then the seed will sprout/O Nanak, without the treatment, the raw fabric cannot be dyed).

The writer Nanak leads us to the art of listening and process of internalising those conversations: ‘Jabb lag dunya rahyyay Nanak, kichh sunneay kichh kahyyay

(As long as we are in this world, O Nanak, we should listen and speak).

However, this process of listening, learning and then speaking (writing) does create ‘occupational’ hazards and the artist Nanak is fully aware and alert to this danger, so he warns his fellow writers and preachers: ‘Dhirrag tinhaa(n) ka jeevya, jo likh likh vaichay naao

(Cursed are the lives of those who read and write the divine’s name to sell it).

Baba Nanak doesn’t just caution us about the ‘business of writing’ but he warns writers about the lurking lust of recognition and rewards too. He declares: ‘Kulhaa(n) dainday baavlay, lainday vadday nilaj/ chooha khudd nah maavee tikkal bannhay chhaj’

(Those who give out ceremonial hats of recognition are fools and those who receive them have no shame/The mouse cannot enter its hole with a basket tied to its waist).

For Baba Nanak truth is the ultimate manifestation of writing. The courage to speak the truth to power is as divine as his connection with oppressed people that is as permanent and unshakable like this verse: ‘Sach puraNa hovay naahi, seeta kadday nah paatay

(Truth does not grow old and when it is stitched, it remains stitched- never to be torn again).

As a Punjabi poet, my introduction to Baba Nanak, the poet, and the artist was through following two lines twenty-two years ago and until today, whenever I read it, I get goosebumps. This rendering starts with a typical Punjabi folkloric opening which is not so common in Baba Nanak’s poetry: ‘Moreen runn jhunn laaya bhainee saawan aaya’

(The peacocks are singing so sweetly, O sister, the rainy season of Saawan has come). And then comes this: ‘Aa’ay nah sakkaa(n) tujh kan piyaaray, bhaij nah sakkaa(n) ko’ay / aa-o subhaagi neendaReay matt saoh daikhaa(n) so’ay’

(I can’t come to you my love and I can’t send anyone to you/ Come to me, O blessed sleep, so I can see my beloved in my dreams).

370 years later, another Punjabi poet Mian Muhammad Baksh carried the same thought forward in these grievous words keeping the Nanaki poetic tradition alive and well: ‘Sufnay day wich milya maahi tay main gal wich paa layya(n) bahnwaa(n)/Dar di maari akh nah kholaa(n) kittay fir vichaR nah jaavaa(n)

(I met my beloved in a dream and I hugged him tightly/ I am afraid of opening my eyes, fearing that I may lose him yet again).

You may have felt that instead of using the more popular epithet Guru Nanak, I have intentionally opted to use ‘Baba’ Nanak. As to me ‘Baba’ signifies a more humane, intimate, closer, humanly equal, and familial ecosystem. ‘Baba’ provides a permanent state of sheltering warmth that’s rooted in the Punjabi rural tradition connecting many generations as one. Baba Nanak himself uses words like ‘banda, Adami, manas’ for himself rather than any other big titles. He is proud of associating himself with lowest of the low: ‘Neechaa(n) anddar neech jaat neechi ho(n) att neech

(Nanak seeks the company of the lowest of the low, the very lowest of the low).

According to Prof Gurinder Singh Mann, Baba Nanak created over nine hundred compositions amounting to 93,302 words and ‘his successors labelled his language as the ‘auspicious language’ (Subhakha, GG 611:19). Mann further adds – referencing the JS Grewal and Irfan Habib edited volume Sikh History from Persian Sources – that ‘the author of the Dabistan-i-Mazahib labels it as the language of Jatts’.

Coming from the Jaangli, Jatki background, I naturally have some reservations accepting that the language of Baba Nanak is those of Jatts. Even when we compare Baba Nanak’s poetic language with Baba Farid and Waris Shah (who belonged to the Baar/Jaangli/Jatki areas like Baba Nanak) we feel a substantial difference in phraseology and vocabulary. More research is required to find out why Baba Nanak didn’t always use the language and expression of the Baar/Jaangli areas. It may well be due to the influence of Vedic texts, Bhagti writings or due to his long travels that his language doesn’t always read like the Punjabi language of the 15th century, as we know it.

Ironically, there are no other known writings of Punjabi available between Baba Farid and Baba Nanak. We have a silent period between these two greats of nearly 300 years as far as documentation of Punjabi poets is concerned, making it more challenging to fully understand Baba Nanak’s lingual trajectory.

There appears very little influence of rural folk tradition and folk love themes on Baba Nanak’s poetry. However, wherever that appears, simplicity and directness of expression makes it feel so contemporary: Here are a few such examples: ‘ Bohta Jeevan manggeay moyaa nah loRay koe

(Everyone begs for a long life, no one wishes to die);

Kammar kataara bankRa, bankkay ka aswaar/garrab nah keejay Nanaka matt serr aaway bhaar

(A beautiful dagger hangs by your waist, and you ride such a beautiful horse/But don’t be too proud, O’Nanak, you may fall headfirst to the ground);

Mandda kissay nah aakheay, paRh akhhar eho bujhheay/moorakh naal nah lujhheay

(Don’t call anyone bad, read these words and understand/ Don’t argue with fools).

Use of word lujhheay here is as natively Jaangli/Jatki as it can ever be. ‘Roopeen Bhukh nah utray, jaa(n) daikhaa(n) taa(n) bhukh/Jeetay rass sareer kay, taytay laggey dukh

(Beauty doesn’t satisfy hunger, when someone sees beauty, hunger increases/As many are the pleasures of the body, so many are the pains which afflict it).

Baba Nanak’s forceful rejection of unjust authority and his love for the downtrodden is as powerful as his divine humility. Here are few such renderings: Haqq paraya Nanaka uss soo’ar uss gaa

(To take what rightfully belongs to others is like a Muslim eating pork or a Hindu eating beef);

Jo ratt peevay mansaa(n) tin kion normal cheet

(Those who suck the blood of fellow beings, how can their consciousness be pure); Raajay sheenh, muqaddam kuttay, jaa jagain baithay suttay/Chaakar naoh’daa paa’in ghao/ratt pitt kuttyo chatti jao

(The Kings are tigers and their officials are dogs; they go out and awaken the sleeping people to harass them/The public servants inflict wounds with their nails; the dogs lick up the blood that’s spilt);

KooR Raja kooR parjaa, kooR sabh sansaar

(False is the king, false are the subjects, false is the whole world).

Baba Nanak is a trailblazer in so many ways, as a poet, he introduced and popularised several Punjabi poetic genres that need a separate space. However, his most powerful work is Babar Baani, the 27 stanzas composed in response to Babar’s invasion and abuses which turned Punjab into maaspuri (city of the dead) starting from attacks on Punjab in 1510 to 1526 when he conquered Delhi. This was when Baba Nanak lamented about Lahore as well when Babar’s forces nearly destroyed it: Lahore sehr, jehr qahr, savva pehr

(The city of Lahore suffered terrible destruction for hours).

Below are few of the verses that summarise how Baba Nanak reacted to the barbaric invasion of Babar on our land:

Paap ki janjj lay Kabuloo(n) dhaaya, joree(n) manggay daan vay Laalo/ sarram dharram doay chhipp khaloay kooR phirray pardhaan vay Laalo/ khoon kay sohlay gaavay Nanak ratt ka kanggoo pa’ay vay Laalo

(O Laalo, bringing the marriage party of sin, Babar has invaded from Kabul, demanding our land as his wedding gift/O Laalo, modesty and righteousness both have vanished and falsehood struts around like a leader/The wedding songs of murder are sung, O Nanak, and blood is sprinkled instead of saffron, O Laalo); Babar Vaani phirr gai ko’er nah roti khaa’ay

(Since Babar’s rule has been proclaimed, even the princes have no food to eat).

Art of poetry and humanitarian message of Baba Nanak is not just restricted to the land of his birth, but it spread across frontiers. It’s believed that Sain Sachal Sarmast (1739-1827) named one of his disciples Yusuf as Nanak Yousuf because his poetry reminded him of Baba Nanak.

Punjabis and the people of the sub-continent need more of Baba Nanak, Baba Farid and Sachal Sarmast to reclaim their long-lost sense of peace and cohesion. Compassion, accommodation and acceptance of the undiluted truth can set this caged region free and there is no better source than Baba Nanak and Sufi Bhagti poets of our land. In Baba Nanak’s own words: Nah maila nah dhundhlaa nah bhagwa nah kach /Nanak laal-o-laal hay sachay ratta sach

(Neither dirty, nor dull, nor saffron, nor any colour that fades/O Nanak, crimson, deep crimson is the colour of those who are imbued in truth).

Published on 26th January 2020 in The News on Sunday.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/603012-the-spiritual-poet